ESG Lab | Supply chain

Complex. Often opaque. A source of significant risk – but with the potential to create value. Ensuring the sustainability of global supply chains presents a thorny challenge for today’s multinational corporations – and it is one that is beginning to be shared by private equity fund managers and their limited partners (LPs). Especially today, where the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed and challenged supply chain organisation, reliance and resilience.

To better understand the issues involved and the specific roles private equity investors can play, PAI Partners held two workshops on sustainable supply chains, in London and New York, in January 2020. Attended by more than 20 participants both in London and in New York, including our investors, portfolio companies, and supply chain experts in the legal and consulting fields, the workshops introduced the key issues involved – and some of the solutions that are emerging.

With the help of real-life objects, such as a wooden toy bus, a t-shirt, an avocado and a hairdryer, we asked groups of participants to travel back up the supply chains of those products and think about the issues that they needed to cover for each. As London’s ESG Lab moderator, Mike Tyrrell, the Editor of SRI-Connect, announced it: “It’s going to be a magical mystery tour that takes you from the garment factories of Bangladesh to the orange groves of Florida.”

Their mission as separate buying departments of a fictional British department store, Sparks & Mencer, was to use experts’ interventions and roundtable discussions to think through:

- What is the nature of this product’s supply chain?

- What are the main environmental, social and governance issues that can be encountered in this product’s supply chain?

- How could we manage those issues with budget and margin constraints? And which ones are we going to prioritise?

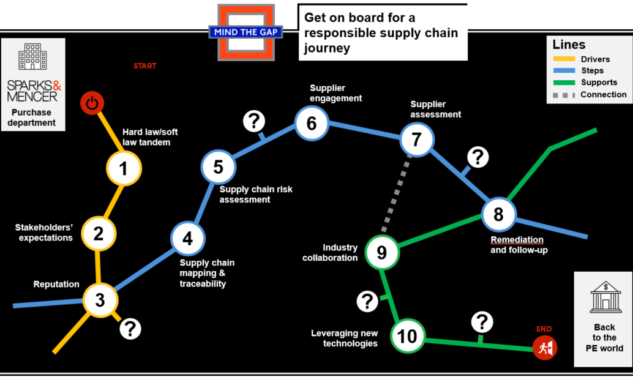

They were helped on this ‘journey of discovery’ by two tools:

- A map – specifically designed by PAI’s ESG team to help them travel through drivers, steps and supports

- Guides – supply chain experts from PAI’s portfolio companies or advisory network who would pop up at different stations and share their experience and ideas with the participants.

In London

Laurence Beck, Head of Quality, CSR and Communications, Wessanen

Catia Cesari, Partner, TAU Investment Management

Erin Lyon, Vice President Sustainability Consulting, Elevate

Minna Lyijynen, Group Manager Sustainability, Refresco

Thomas Radal, EU Representative, Ulula

In New York

Maud Brown, Partner and Head of US team, PAI Partners

Guillaume De Vesvrotte, Co-Founder, We Don’t Need Roads

Antoine Heuty, Founder & CEO, Ulula

Oliver Niedermaier, Founder & CEO, TAU Investment Management

Marianne Voss, Supply Chain Compliance Lead, Malk Partners

Kristina Wyatt, Senior Counsel, Latham & Watkins

The reality of supply chains

In today’s globalised, connected world, a large proportion of a company’s ESG exposures is often to be found beyond its operations, in its value chain. They range from climate physical risks, degradation of environment, human rights infringement – with their worst embodiment in modern slavery, bribery and corruption. Despite a lack of direct control, the sourcing company will be held at least partially responsible if – or, more likely, when – they materialise.

“This is not about risk – it’s about dealing with a reality that is going to hit you at some point”, said Cornelia Gomez who, prior to joining PAI to manage its ESG team, was Social Compliance Manager at Groupe Casino, auditing factories in China, Bangladesh and other at-risk countries. Supply chain exposures can add costs, jeopardise business continuity and, in extreme cases, have severe reputational damage, thereby threatening a company’s social licence to operate.

Despite the growing list of supply chain disasters – the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh in 2011, suicides at Apple supplier Foxconn, controversies around conflict minerals and modern slavery – investors have too often been behind the curve on supply chain management.

Hard and soft law

In addition to reputational and business continuity risks that can be found in supply chains and which have become all too apparent in the current context, investors and their portfolio companies face regulatory and litigation risks, with a growing body of ‘hard law’ that is emerging to complement the ‘soft law’ of industry codes of conduct.

These laws include the UK’s Modern Slavery Act, France’s Law on the Duty of Vigilance, and the US conflict minerals provision of the Dodd Frank Act. Despite this latter legislation, there is a gulf between the increasingly standardised, rules-based approach in Europe and a more ‘hands-off’, principles-based approach from US regulators, noted Kristina Wyatt, Director of Sustainability at global law firm Latham & Watkins. “The challenge here is that investors want comparable information and they are not getting it.”

The sustainable supply chain journey

As participants of our ESG Labs journeyed along the supply chain, they came to realise that supply chain mapping and risk assessment are unavoidable steps of the process. Achieving full traceability of a supply chain is nearly impossible and the result of a continuous improvement process starts with collaborative work between different teams.

Companies first need to understand how their supply chains are structured, where raw materials, components and products are extracted or produced, in what country and by whom. That can place a considerable burden on companies and investors alike. However, understanding every step of the value chain will not only facilitate risk identification and mitigation, it will also serve to maintain and foster supply chain sustainability.

Once suppliers are identified and mapped, the subsequent data collection and audit challenge can be considerable. Not only might a company have hundreds of direct suppliers, their tier 2 and 3 suppliers can multiply that figure. In addition, suppliers can use so-called ‘window factories’ without the knowledge of the purchaser – and these may fail to meet mandated labour or environmental standards which the direct suppliers comply with.

Even deciding on which audit standards to apply can be challenging: as one speaker noted, there are literally hundreds of different types of codes of conduct and ethical audit, and they are proliferating at a rate of around 10% each year. The audit processes themselves can prove inadequate if the data submitted is not up to scratch: in China, 50% of audit data is falsified, according to some estimates.

This reinforces the case for industry collaboration. Given the complexities of supply chains, there is considerable potential for duplication of effort, with suppliers finding themselves subject to multiple audits, which can often require them to source and submit different information.

How technology can help

Technological solutions are emerging that can support these processes. For example, healthy food company Wessanen, a PAI company, uses the Sedex transparency platform to ensure that its suppliers pursue ethical labour practices. And Ulula, a Canada-based social enterprise, has developed a solution, Worker Voice, that engages with workers directly and anonymously to allow them to report incidents or maltreatment in the workplace.

It’s not just about cost, however. Investing in supply chain transparency can deliver co-benefits to supply chain stakeholders. The workshops heard how Refresco, the world’s leading independent bottler for retailers and branded beverage companies, and a PAI portfolio company, has worked with Dutch retailer Albert Heijn and leading orange juice supplier LDC Juice to deliver a blockchain-based tracking system for Albert Heijn’s own-label orange juice. The system allows customers to scan a barcode to learn about the provenance of their juice, and even send messages to the growers.

“It is a way to use modern technology to recreate the connectivity that existed in the past between the grower and the buyer,” said Maud Brown, PAI’s Head of US. “As an investor, it’s very interesting to convert something that was a risk management concern, about product traceability, into a virtuous circle where we can drive greater employee and customer engagement as a result of caring about sustainability.”

Investors can bring a fresh set of eyes to supply chain exposures and provide an opportunity to ask targeted questions that can help to mitigate risk: the workshops heard about how PAI’s due diligence process when investing in games maker Asmodee led to a plan of action to ensure the appropriate governance, policies and processes were in place to better manage its supply chain sustainability.

An investment opportunity

While these efforts can be a cost to companies and their investors, this issue also presents investment opportunity. TAU Investment Management, a specialist investor in the apparel and textile value chain, uses sustainability and technology to create competitive advantage in its portfolio companies, explained Oliver Niedermaier, its Chairman and CEO.

“There is a huge opportunity to be found in investing in leading tier 2 suppliers,” helping them upgrade their technology, apply advanced manufacturing and digitised value chains, and upgrade management, he said. “Because of our proprietary deal pipeline and sector expertise, we can invest in them at reasonable multiples and expect significant multiple uplift at exit, because they can earn a sustainability, scale and technology premium.”

Looking ahead

The fundamental message from the workshops was that, while supply chain ESG risks are extensive, complex and difficult to effectively assess, there are techniques, tools and technologies available to help, and pathways to collaboration that can help to efficiently spread the burden.

We are therefore pleased to announce that PAI’s ESG team is releasing a Sustainable Supply Chain Guide that will be published as a series over the course of the next months with a recap of key take-aways in our annual Sustainability Report.

This guide is aimed at private equity investors (both LPs and GPs), other institutional investors, and corporate sustainability specialists. It offers an introduction to the subject of supply chain sustainability and advice on useful approaches, principles and processes. For example, readers will also find a cheat-sheet with questions to ask in the due diligence phase and toolboxes for each step of supply chain monitoring. While it is based on the two workshops mentioned above, we have also leveraged our direct experiences with portfolio companies, and an exhaustive literature review.

So stay tuned!